The Tragic Tale of the SS Daniel J. Morrell Shipwreck in November 1966

Would you like to save this full guide?

The Great Lakes have been used to transport people and resources for hundreds of years. From canoes to steamer ships to modern freighters, all kinds of boats have braved these dangerous, unpredictable waters. Unfortunately, not all of them have made it to their destination.

It’s estimated that 6,000 vessels have been lost to Great Lakes storms, and about 1,500 rest beneath the surface of Michigan waters. The SS Edmund Fitzgerald may be the most famous of these, but another tragic shipwreck with an interesting story is that of the SS Daniel J. Morrell.

In this guide, we’ve gathered as much info as we could about the SS Daniel J. Morrell shipwreck to share this tragic story and remember the crew who lost their lives in November 1966.

The SS Daniel J. Morrell: A Steel Giant of the Great Lakes

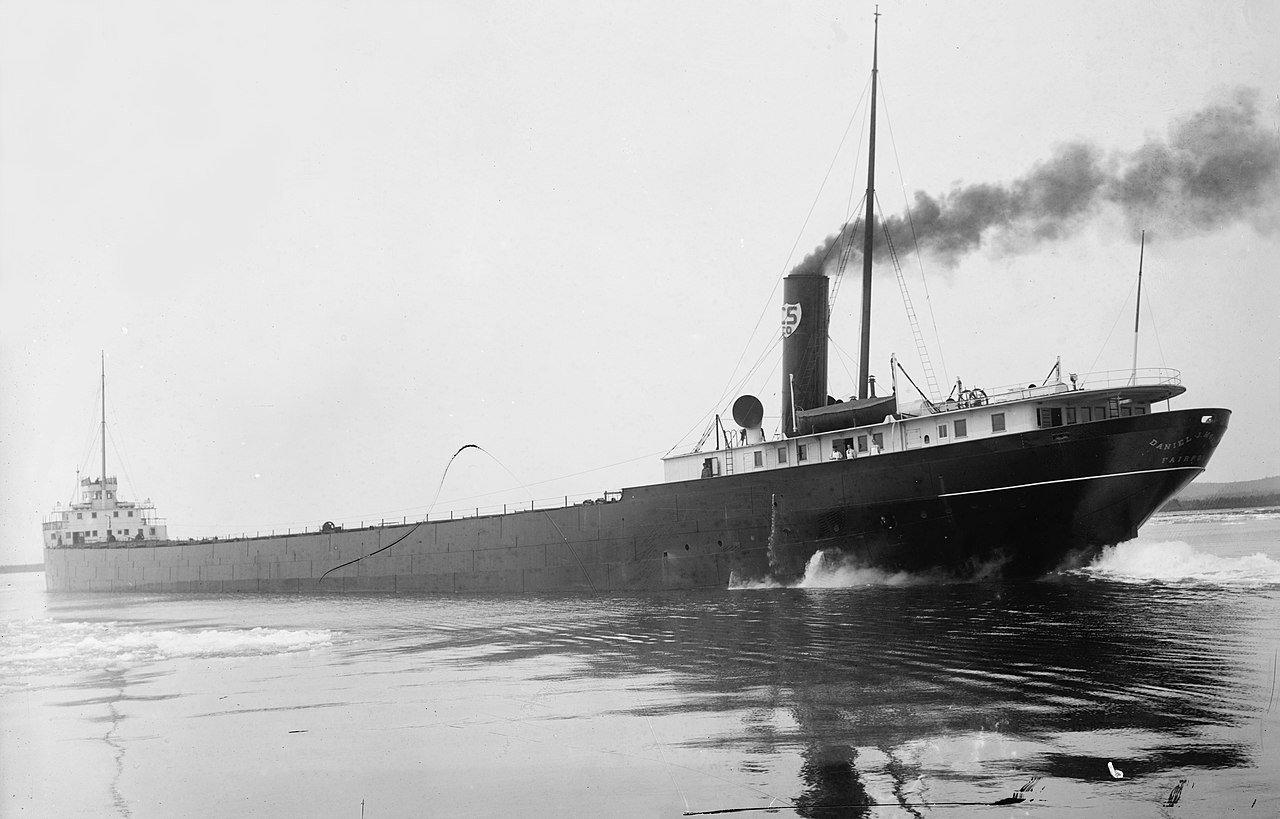

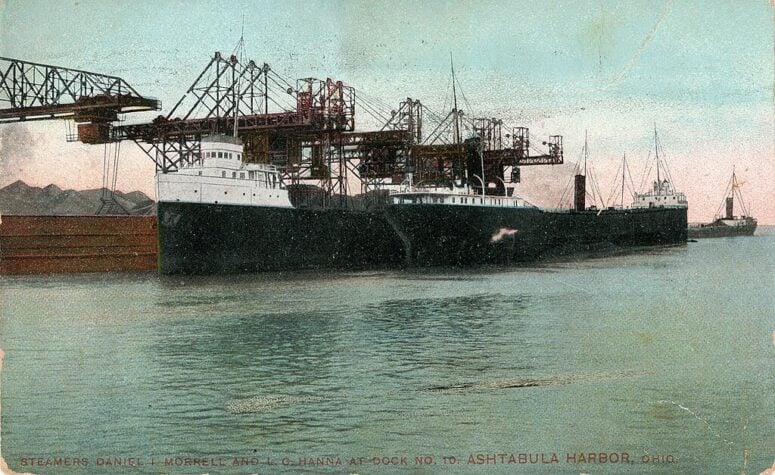

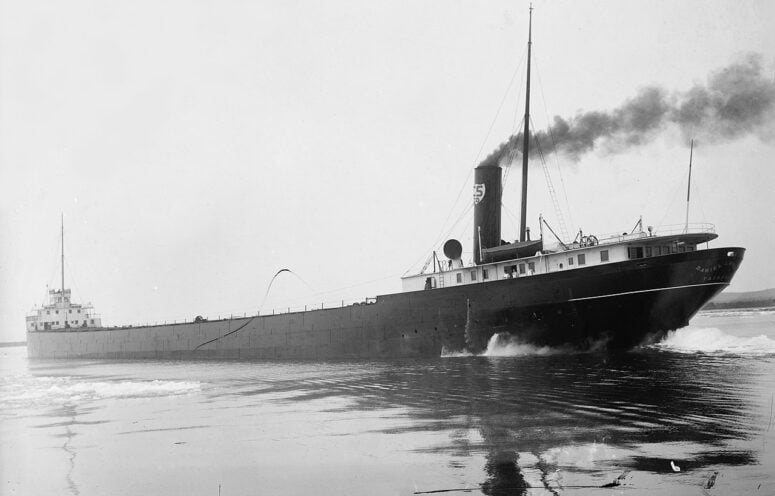

Built in the early 1900s by the West Bay City Ship Building Company, the SS Daniel J. Morrell was launched onto the Great Lakes in 1906. It was named after U.S. Pennsylvania Representative Daniel Johnson Morrell.

The steel ship was one of the biggest bulk carriers of the time at 603 feet long and 12,000 tons heavy — just like its sister ship, the SS Edward Y. Townsend, which was built by Superior Shipbuilding Company.

Both were operated by the Cambria Steamship Company and often “sailed” together, transporting bulk cargo such as coal, iron ore, limestone, and grain to ports along the Great Lakes.

The Ill-Fated Final Run of the SS Daniel J. Morrell

On November 29, 1966, the SS Daniel J. Morrell and SS Edward Y. Townsend were making their last transports of the season together on Lake Huron when disaster struck. A storm picked up with wind speeds of up to 60 mph and waves soaring more than 25 feet high — although some accounts say the swells reached up to 35 feet.

While the Townsend decided to hang back and seek shelter in the St. Clair River, the Morrell kept going and headed toward Thunder Bay for protection. It was only carrying ballast at the time, rather than its usual heavy cargo. Unfortunately, the electrical cable on board broke, so the crew couldn’t transmit a distress call.

With the ship being battered by the storm, the crew was forced onto the deck and many of them jumped to their deaths in the 34-degree water. The early 1900s steel was no match for the elements, though, and it didn’t take long for it to split in half as the remaining crew loaded into a raft.

As the bow quickly sank, what the crew thought was another ship was actually the Morrell’s aft — still powered by the engine — heading straight for them. Shortly after the bow sank, the stern followed, slowly slipping into the dark waters of Lake Huron.

The Lone Survivor

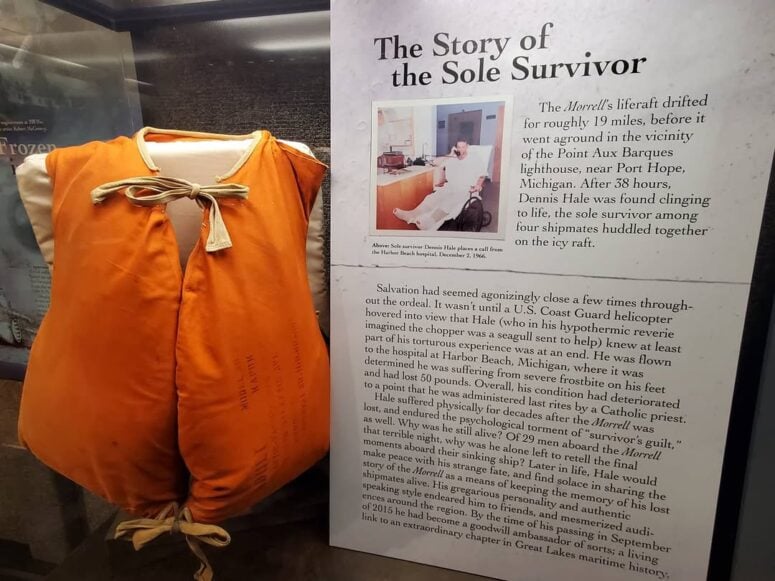

Since the SS Daniel J. Morrell couldn’t send out a stress signal, the U.S. Coast Guard didn’t send search parties out until after the ship was reported missing the following afternoon, November 30. It was 14 hours before they found Dennis Hale, a deck watchman and the only survivor of the SS Daniel J. Morrell shipwreck.

From Ashtabula, Ohio, he was just 26 years old at the time. A helicopter pulled him from his life raft, and all he had on was his pajamas, a pair of boxers, and a peacoat over his life jacket. It was a miracle that he survived for almost 40 hours in the frigid, snowy weather. Because of a broken ankle, severe frostbite, and long-term physical trauma, he had to have more than 12 surgeries.

What might be the most horrifying part is that he wasn’t alone on the raft. He was found with ship captain Crawley, first mate Kaptis, and second mate McCloud, each of whom froze to death one by one.

Hale lived almost another 50 years after the shipwreck, passing away from cancer at the age of 75 in September 2015. Before his death, though, he published “Sole Survivor,” a book that detailed the events of the tragedy. Following the Morrell shipwreck, though, he was interviewed by The Bay City Times, which wrote:

“I was asleep when I heard a hard thump,” he said. Books in his room tumbled to the floor. The lights blinked out.

“I thought the anchor was dropping,” he said. “Then I heard the emergency alarm. I got dressed and ran topside. The ship was breaking in half.”

Hale clambered into a pontoon liferaft (sic) with the ship’s captain, Arthur I. Crawley; First Mate Phil Kaptis and Second Mate Duncon McCloud.

“As we were floating out on this raft we could see the two halves hitting each other,” he said. “They had separated, and the back part still had power and kept ramming the front part. She buckled, and she sank.

“About 15 minutes after we got on the raft, the ship went down. The last thing to go down was the stern. I saw it slowly slip into the dark waters.”

Two of his companions died shortly after dawn Tuesday, he said. The storm still raged.

“They died within minutes of each other,” he said. “Their lungs began to fill with water. The third man died the same afternoon.”

Snow kept falling. Raging winds tossed the raft like a stick. Hale burrowed beneath the three bodies for warmth. He put his hands inside his jacket against his body to keep them from freezing.

He waited.

“The sea was a terrible rage,” he said. “There was no sunshine.”

Hale slipped in and out of consciousness. But he roused when a helicopter appeared Wednesday, nearly 36 hours after he boarded the raft.

The Townsend Later Suffered the Same Fate

Although the SS Edward Y. Townsend, the sister ship of the SS Daniel J. Morrell, sought shelter in the St. Clair River nearby, it didn’t escape the November 29, 1966, storm without sustaining damage. The ship was able to finish its transport afterward, but it had a huge crack in it. Because of that, it was deemed unfit for operation and permanently docked.

Eventually, the Townsend was sold to a European scrap company and suffered the same fate as the Morrell. It split right in two when a storm developed while the ship was being towed across the Atlantic Ocean.

The SS Daniel J. Morrell’s Final Resting Place

When a survey was done on the wreckage of the SS Daniel J. Morrell, the bow and stern were confirmed to have split apart. They came to rest just beyond the northern boundary of the Thumb Area Bottomland Preserve — slightly north and east of the Michigan Thumb — about 220 feet underwater among more than 20 other major shipwrecks.

Since the two sections completely split from each other, they didn’t land right next to each other. Initially, investigators didn’t believe the recollection of Dennis Hale when he said that the ship split and that the engine was still moving the stern until it sank.

However, during a survey by investigators, the time on the ship’s clock indicated that the stern kept moving on its own for nearly 90 minutes before it completely went down. As a result of that continued movement, it lies at the bottom of Lake Huron about 6 miles from the bow.

Despite that and being at the bottom of Lake Huron for more than 50 years, the SS Daniel J. Morrell is remarkably intact. The bow’s cabin, mast, and mushroom anchors and the stern’s lifeboats, life ring, galley dishes, smokestack, and double wheel are all still intact.

Experienced, Technical Divers Can Visit the Wreckage

Because of where the SS Daniel J. Morrell lies, it’s possible for divers to visit each half as long as they have the right experience. The stern is located at N 44° 15.478 W 082° 50.088, while the bow is located at N 44° 18.320 W 082° 45.161.

You don’t have to go alone, though. There are a couple of diving services in the area. Below the Grade Scuba has a dive boat — called The Ho-Hum — that features the first diver elevator on the Great Lakes. Also, rental equipment is available upon request.

Another option is Double Action Dive Charters, which runs The Go Between on Lake Huron between Harbor Beach and Port Sanilac. It can accommodate a group of up to 16 divers, and fresh fruit and water are included.

The Captain & Crew of the SS Daniel J. Morrell

In remembrance of the 28 crew members who lost their lives in the SS Daniel J. Morrell, we’ve compiled a list of them here in alphabetical order. Each is listed with their name, station on the ship, age, and place of residence (as long as the info is available). Of these men, only three bodies were never recovered.

- Norman M. Bragg — a 40-year-old watchman from Niagara Falls, New York

- Stuart A. Campbell — a 60-year-old wheelsman from Marinette, Wisconsin

- John J. Cleary — a 20-year-old deckhand from Cleveland, Ohio

- Arthur I. Crawley — the 47-year-old master captain from Rocky River, Ohio

- George A. Dahl — the 38-year-old third assistant engineer from Duluth, Minnesota

- Larry G. Davis — a 27-year-old deckwatch from Toledo, Ohio

- Arthur S. Fargo — a 52-year-old fireman from Ashtabula, Ohio

- Charles H. Fosbender — a 42-year-old wheelsman from St. Clair, Michigan

- Saverio Grippi — a 53-year-old coal passer from Ashtabula, Ohio

- John M. Groh — a 21-year-old deckwatch from Erie, Pennsylvania (never recovered)

- Nicholas P. Homick — the 35-year-old second cook from Hudson, Pennsylvania

- Phillip E. Kapets — the 51-year-old first mate from Ironwood, Michigan

- Chester Konieczka — a 45-year-old fireman from Hamburg, New York

- Duncan R. MacLeod — the 60ish-year-old second mate from Gloucester, Massachusetts

- Joseph A. Mashem — a 59-year-old porter from Duluth, Minnesota

- Valmour A. Marchildon — the 43-year-old first assistant engineer from Kenmore, New York

- Ernest G. Marcotte — the 62-year-old third mate from Waterford, Michigan

- Alfred G. Norkunas — the 39-year-old second assistant engineer from Superior, Wisconsin

- David L. Price — a 19-year-old coal passer from Cleveland, Ohio (never recovered)

- Henry Rischmiller — a 34-year-old wheelsman from Williamsville, New York

- Stanley J. Satlawa — a 39-year-old steward from Buffalo, New York (never recovered)

- John H. Schmidt — the 46-year-old chief engineer from Toledo, Ohio

- Charles J. Sestakauskas — a 38 or 39-year-old porter from Buffalo, New York

- Wilson E. Simpson — a 50-year-old oiler from Albemarle, North Carolina

- Arthur E. Stojek — a 41-year-old deckhand from Buffalo, New York

- Leon R. Truman — a 45-year-old coal passer from Toledo, Ohio

- Albert P. Wieme — a 51-year-old watchman from Two Harbors, Minnesota

- Donald E. Worcester — a 38-year-old oiler from Columbia Falls, Maine

Learn More About Michigan Shipwrecks

The tale of the SS Daniel J. Morrell shipwreck is a combination of tragic, horrifying, and harrowing yet interesting all at the same time. But, it’s far from the only wreckage on the floors of Michigan’s Great Lakes waters.

You can learn more about the state’s shipwrecks at museums like the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point and the Great Lakes Maritime Heritage Center. And, if you’re not a diver, consider booking a glass bottom shipwreck tour on Lake Huron or Lake Superior.